Infinite Rest

The entrance is on Broadway and 10th, where the street takes a slight left to begin its slanted carve. At the northeast intersection is Grace Church, an ornate marble parish built in 1843, whose Gothic Revival exterior stands in supercilious contrast to the cast iron and glass box buildings around it.

Everything about this church should stand out. It is replete with a striking steeple whose placement at Broadway’s kink makes it appear from the south as a tower on the vanishing horizon, discernible from over a half-mile away. On weekends it hosts public recitals of traditional repertoire and hymns on its four-keyboard, 76-stop, 87-rank organ, where thousands of pipes invisibly flood the nave with deep, resonant sound. It’s a block south of the Strand, located within the triangle enclosed by Union Square, Washington Square Park, and Astor Place, surely the three most pestiferously adolescent locations in Manhattan. But most walk past it, focused instead on what’s ahead, with errands to run and friends to find, overstimulated enough as is. Their eyes, kept at street or screen level, have no chance of noticing the pinnacles.

You enter through a side gate and walk down a short path past a front yard of cherry blossoms and well-groomed hedges, a petite hortus conclusus. Past the stone archway and to the right is the nave. Unfortunately, requesting to use the entire church would be unwieldy and unnecessary; we use another space entirely. In fact, there is a school at the end of the hallway, fused into the side of this structure, founded by the Church over a century ago. Matt Yglesias attended it, Wikipedia says. Less than a hundred feet from the altar is an indoor half-gymnasium with folding bleachers in lieu of wooden pews, illuminated by fluorescent lights instead of stained glass. That is where, once a week, my choir rehearses.

On Tuesday nights, a hundred recent grads and retirees alike commute in, don their nametags, and pack together to sing for two and a half hours. I want to say that I’m a relatively faithful member of this group. It doesn’t take me long to memorize the music (and I review at home if needed), I’m pretty good at following cues, and I only look at my phone occasionally. Still, I can’t help but get distracted when my part isn’t practicing, or during the pauses between measures when pages are turned and throats are cleared. My thoughts wander.

I entered my final year of undergrad with a “victory lap” mindset, which I could barely believe. Since high school, or really since becoming self-conscious, I’d been obsessed with the collectibles: hard courses, intensive projects, resume trinkets. Suddenly I had a job offer and, incredulously, a weak sense that I’d more or less satisfactorily explored the academic path I had wanted to follow in college. This was completely foreign to my usual drive, one that was equal parts competitive and directionless. I had not given myself the autonomy to prioritize fun for most of a decade.

During the first week of the year I let my eyes wander, and it was not long until I spotted posters advertising auditions to join a chorus. Only a five-minute first-round audition, they said, a quick voice test. We’re inclusive and open to a range of skill levels. Don’t listen to Lord of the Flies. Sign up here, please?

Prior to this, my experiences with singing had been a couple hundred hours of shower karaoke and several afternoons of Rock Band on the Xbox. Certainly I could and might as well have tried. Time- and effort-wise, spending five minutes out of a weekday afternoon cost basically nothing. The real challenge, as with a remarkably many number of things in general, was the psychological overhead of being open to embarrassing myself and risking vulnerability by doing something I didn’t excel at, a premise my mindset had long ago fortified itself against, even with nothing to lose.

It goes without saying that the auditions went well, and the rest was history. At the end of the day, I was just screwing around. Serendipity redeems itself sometimes. It can be addicting. When it happens you feel like a lucky bastard. You revel in chance, extol the elegant unpredictability of the side quest, the butterfly effects in your own life. The caveat is that you can’t become dependent on it, for if you were to wait for good luck to roll into your lap then you’d have to be sitting still. But we shouldn’t entirely reject the high either. Optimize your life, rid it of any degree of uncertainty, and you’re closing yourself off to the kind of elevating variance that comes with ceding control and letting go. The strategy seems to be, in addition to finding some golden mean, to increase your luck. I don’t know exactly how to do that yet, but my intuition tells me it’s probably a counterintuitively methodical process. There’s an art to screwing around.

We are singing Giuseppe Verdi’s Requiem, and have hired an orchestra to accompany us for the concert. It’s a well-performed piece, probably one of the most mainstream large-scale choral works in the standard repertoire.

A Requiem is one of the oldest musical formats you can find. It is a Mass in remembrance of the dead, originally used in liturgical context. The solemnity and gravitas of its reverent and at-times apocalyptic Latin text, combined with centuries of musical precedent, has enshrined it as one of the most profound endeavours a composer can tackle. Among other remarkable examples, there’s Mozart’s ill-fated masterpiece, his symphonic monument to the dead forever shadowed by the circumstances of his own passing; Faure’s restrained and concise suite with its hauntingly pure solos and subtle moments of momentous force; Britten’s dissonant and unsettling behemoth with raw settings of English war poems scattered recitatif within movements. To compose a Requiem is to confront and harness the divine mystery of death, to construct a personal conception of the spiritual in order to express it, and imbue your music with that character and the character of your time. All this, to begin with the same hallowed words: requiem aeternam. Eternal rest—infinite rest.

Verdi’s case is particularly interesting, as his Requiem is essentially his only well-known non-operatic composition. His oeuvre, featuring hits such as La traviata, Aida, and Rigoletto, is unquestionably his main claim to fame otherwise. His works stand at the high water mark in the genre, defined by their deft coloratura writing and emphatic drama. With his contemporaries like Bellini, Puccini, and Rossini, he helped define a clear and celebrated form of Italian opera, a form of spectacle, virtuosity, and charm that stood in distinct contrast to his German contemporaries’ oft-serious and faintly arrogant Gesamtkunstwerk. And while it was ostensibly never explicit, it would be hard to argue that his music didn’t fuel the tide of romantic nationalism that fueled the Risorgimento: there is no performance of Va, pensiero that doesn’t leave chorus and audience alike feeling ever-so-slightly more patriotic.

So when it came to the Requiem, Verdi, consciously or not, produced something more like an oratorio than a mass. He asks for four soloists, each given judicious time to shine in stellar arias and intricate, ornamented quartets. In between, the chorus works its magic, and this is where the most powerful and well-known parts of the work are found. There’s the double-fugue of the Sanctus, whose bright brass proclamations and boisterous chromatic conclusion pack a jubilant punch that feels much longer than its mere 2½-minute runtime. Then there’s the other fugue, near the very end during the Libera Me, which features the soprano singing near the top of her range about the Last Judgment and the end of the world, pleading to the Lord for salvation in shattering vibrato while the choir plows through some infernal counterpoint.

By far the most dramatic and memorable part of the work, though, must be the opening of the Dies Irae. Four massive and petrifying hits in G minor, punctuated by thuds of the drum, lead instantly to calamitous descending runs of the woodwinds and an upward swell in the tenors and basses, joined then in full force by a shrill howl from the entire choir with the whole orchestra in tremolo (literally trembling). Day of wrath, day of reckoning, the world turned to ash. The section is instantly recognizable, a movie moment, a clip I’ve seen used in TikTok posts. Verdi himself must have foreseen the viral potential of this bit, for he repeats it thrice.

Virality is both immortalizing and reductive, and the flip side of the Dies Irae chorus being so popular is that it masks the rest of the work, so that when one thinks of the Requiem they often only think of this two-minute section, just as Beethoven’s titanic 9th is really just the Ode to Joy, and the 15-hour Ring Cycle is really just the Ride of the Valkyries. The nuance in classical music necessitates replay but also makes it harder to digest with our increasingly incontinent attention spans. That makes it hard to appreciate, on a single listen, all the nooks of beauty to be found in a piece like Verdi’s: the heroic entries of the soloists in the Kyrie like a movie cast assembling, the lush and soaring tenor lines in the Ingemisco, the lullaby-like variations of the Agnus Dei, the glistening ebullitions of the flutes in the Lux Aeterna…

Fascinating, too, is the historical context. Verdi originally meant, upon the death of Rossini, to assemble a collaborative Requiem, thirteen Italian composers each writing a section. And he did so, but less than two weeks before its scheduled premiere, the concert was abruptly cancelled due to reasons which we might today describe as “beef” between Verdi and the conductor. The Requiem for Rossini would go unperformed until 1988, after its rediscovery.

It would take a few more years until Verdi became compelled to tackle the task solo, the motivation eventually coming from the death of the writer Manzoni. Verdi took his original movement, the Libera Me, and expanded it into a full work. The Church hesitated on his inclusion of female soloists, for women were not allowed to sing in Catholic rituals at the time; Verdi disregarded them. Critics thought the work too operatic for its subject matter and pointed at the use of parallel fifths, and I imagine Verdi disregarded them, too. During the Holocaust, prisoners in the Terezin concentration camp learned the Requiem off a single score and piano as an act of defiance. The Met Opera performed it on the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks.

For such a staple of the canon, now steeped in well over a century of historical significance, I cannot help but find it a little funny that the composer of this piece, when his name is literally translated, is called Joe Green.

My previous ventures into music performance had resulted in markedly more ambivalent outcomes. For half a decade I banged away at an upright Yamaha in the living room of my home. In middle school I walked into music class and was given a baritone horn because that was the only instrument that nobody else knew how to play. In high school I walked into band rehearsal and was given a tuba because that was the only instrument that nobody else had chosen yet. Thus I am well-trained.

I was a stronger pianist by nearly any metric. The Royal Conservatory of Music, which is Canada’s supreme authority on musical pedagogy, defines ten levels of progressive advancement in their piano certificate program, concluding in an associate diploma. To complete a level you took a practical exam where you’d play a program of repertoire pieces and perform technical drills. Passing certain levels also mandated the fulfillment of coincident theory requirements as assessed through standardized tests. Since an education in classical music is one of the best things you can do for your children cognitively, or whatever, my parents thought it indispensable that I, too, receive a rigorous training. Thus for a considerable stretch of my adolescence, I would be driven to harmony and history classes held in strip malls on weekend mornings and to 45-minute private lessons in the suburbs on weekday evenings. Every few months I would offer satisficing renditions of the etudes I had prepared for examiners and write Royal Conservatory tests in packed church halls. All this took me to Level 10 of the program. At the height of my powers, I could show off some of the easier Chopin pieces, harmonize a quartet from a single leading voice line, and effortlessly disgorge a thousand-word essay on madrigals.

By contrast, my high school band was powered mostly by enthusiasm and community—enough to make for one of the more pleasant parts of my sophomoric years, but nothing in comparison to the force of nature that is a Asian parent’s benevolent resolve. One year at a local festival, the band director made the mistake of programming a piece with a tuba solo. In the recording provided to us afterward, you can hear the saxes and trumpets finishing their phrase, ending on an anticipatory chord, and then, in time for the solo… absolute silence. Well, not absolute silence: you can hear one of the judges saying “uh, okay”. I could not even buzz loud enough to be heard; I never built up the lungs.

Despite my lack of talent in the latter, there was scarcely a time where I preferred the piano to whatever brass instrument I was screwing around with. Part of this was simply a matter of joy. I preferred playing with friends, without the pressure or prescribed discipline. But it was not so much a matter of the joy I had swinging around a tuba than it was the noticeable dearth of joy I had on the keyboard. One characteristic of attending an archetypal locally-competitive, second-generation-immigrant-Asian-plurality, upper-middle-class-suburb school means that almost everyone you knew played some instrument extracurricularly, and played it seriously. Among the contingent of my peers who played the piano, I had begun relatively late and was close to the bottom in terms of skill. Some had already received their associate diploma when I was starting lessons, prepubescent kids reciting the Pathétique and Ballade No. 2, completing what is viewed as essentially an unofficial equivalent to university coursework before their hands had grown to their full size. Upon receiving the diploma, that was it. You had a well-defined and accredited accomplishment to add to the arsenal; time to move on to other ambitions. Many stopped playing piano afterward. This was an environment of talent that had been commoditized and saturated to the point of absurdity. Even with an associate diploma you were not special, unique, or outstanding; without one you were inferior. It was hard to develop a love of the game when the game was de facto a completion-based one, and one that those around you had completed years ago at that.

I don’t think it’s an inflammatory claim to say that this is not how music education should be. Music ought not be a rote curriculum to be planned optimally and finished as quickly as possible in the way that one, say, tries to file their taxes. Sure, classical musicians compete internationally just as athletes contest championships every year, and both undergo extraordinary lengths to hone their craft. Yet it would be odd, teleologically incorrect in fact, to say that an Olympic medalist has “completed” their sport. Sports are not things to be finished, and nor is music. Standardization is crucial for giving students accessible and objective goals to work against, and on the whole democratizes access to a what remains fairly gated subject. Likewise, I recognize that discipline and discomfort are required for progress, as they are nearly everywhere. My core qualm has more to do with the provenance of motivation here, the bastardization of intention. By treating art too academically and by viewing it strictly through the lens of competition, we strip it of the very value it is meant to bring. We preclude the organic and the human that brings out the best in us, that small, unimpressive realm of shitty-yet-authentic indie playlists, off-tune common-room jam sessions, and rambling blog posts. Our persistent emphasis on classical music qua academic achievement mechanism is very plausibly why we have this stereotype of the nerdy and off-putting but genuine band or choir kid, but such personalities scarcely exist among the top young musicians. It must contribute, too, to the persistent air of superfluous seriousness and elitism surrounding the discipline, whereupon we think you can’t fully appreciate the genre unless you’ve “put in the work” to learn it.

The solution is obviously not to stop teaching classical music. That won’t stop the gatekeeping, and probably the research about cognitive benefits or whatever holds some water. Good extracurriculars, like good hobbies, should serve as gateway drugs to a richer and more diverse appreciation of life, and some paternalistic nudging to learn one’s rudiments can be conducive to that. However, our current model that fetishizes excellence and discounts nearly everything else is not sufficient. The best artists, or the artists who love their art the most, not only have a natural knack; they thrive in the place where passion meets rigour and intuition lines up with skill, where there is that love of the game. I am not claiming to be an exceptional artist (though I can dream), but I’m fortunate enough to have found something that ticks those boxes. It turned out, for me, to be choral singing, where the individual becomes indispensable to yet indistinguishable from the whole, where the atmosphere of collaboration and camaraderie provides a respite from and welcome foil to a world that worships individual success. It just took time to find it.

The choral scene in New York City is broad but remarkably fragmented. It comes alive every weekday evening in church halls and practice rooms, out of sight and out of earshot, humble and isolated, where groups modestly gather, content in their own presence. There’s little overlap in membership, no real forum for choruses to advertise and interact with each other, and no real reason to. Every other week it feels like there’s a performance of a fantastic work with dozens or hundreds of singers, but surprisingly few people in the choral scene are aware.

The recreational choir stands at one end of the spectrum of organized singing. On the other end stands professional choirs, where singers, aside from doing solo gigs or teaching work, are often employed under the auspices of a church or other similar entity, much of the profession being simply a side effect of religious life. Aside from concerts, it is only those kinds of organizations which have regular and predictable demand for choral services, so it’s the case that there isn’t much space, regardless of the singer’s own beliefs, for secular programming. One rehearsal a singer tells me about some contract work he would be doing out in the Hamptons. Some congregation would drive him out each weekend, offering lodging and food.

As with many other creative fields, music performance is necessarily two-sided: you must absorb your own product. Rehearsals train not only the voice but the ear, and just as a chef should taste their own cooking or a writer should revise their own writing, a choir must have a sense of how they sound in order to improve upon it. However, the line between production and consumption is uniquely blurred here, because when you sing, you sing with a group you’re also simultaneously listening to, a two-way process where you continuously consume the output of others in addition to yours—and unlike an orchestra, where solo practice is helpful and expected, almost all the practice is communal, because the strength of an individual singer matters far less than the sound of the collective. Witnessing and contributing to this synergy makes choir uniquely social in classical music performance. While it’s true that the goal of every season, i.e. the concerts, provide outside entertainment value to the world, there’s a lot more internal entertainment that its members can selfishly reap for themselves.

The choir better enjoy their own singing, anyway, because as far as creative fields go, the production to consumption ratio is abysmal. A concert might last one or two hours, but the preparation required for it, especially for amateur ensembles that can’t sightread scores, easily takes weeks and tens of hours per performer. Writing an article online might be a slog, but it pays itself back if it reaches a sizeable audience; pop artists obsess with teams of industry professionals to craft a three-minute hit, but those three minutes might be played billions of times; a software engineer need only write code once before deploying it to impact users worldwide, hopefully for the better; all of these ratios are much smaller than one. For a volunteer choir that doesn’t produce recordings, though, there is no such scale. The concert happens once. The ratio is much larger than one. Consequentially, choir is a prime example of an activity that doesn’t scale.

Maybe this is intentional, an acknowledgement that the value we capture cannot and should not be quantified in terms of numbers but rather lived experiences, and an accepting surrender to the phenomenon of ephemerality that music performance encapsulates so well: organized sound in organized time, a structured rebellion against noise that happens once and then is forever over.

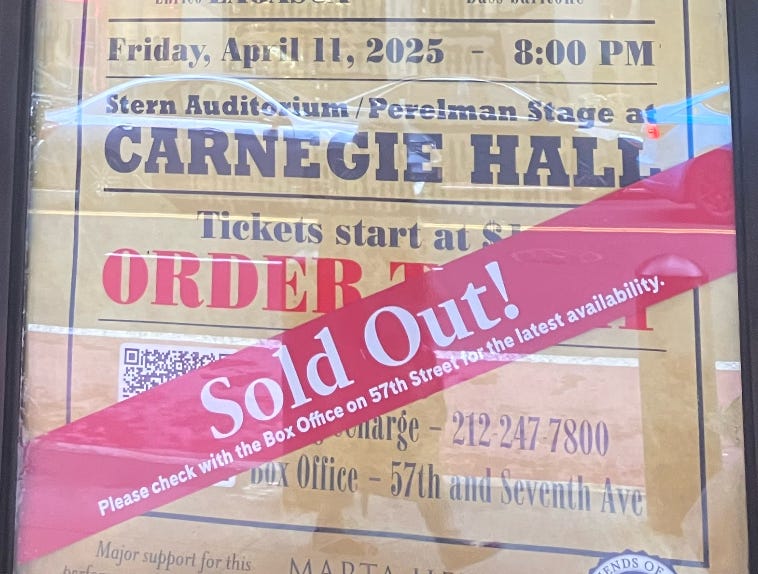

About every two years, our choir builds up enough capital to have some real fun, and rents out Carnegie Hall’s Stern Auditorium for a night. I join just in time for one of these seasons, coincidentally enough, and I feel, a little sheepishly, that I have unwittingly opportunistically hopped on the bandwagon. Propelled by the choir’s large membership, we manage to sell out the show. I do my part to sell tickets, though with my upbeat messages and fervent group-chat pings, it feel as if I am fundraising for a marathon. “Watch us sing Verdi at a sold-out Carnegie Hall!” Quite the narrative soundbite, inevitably somewhat of a boast, maybe not the most sincere.

I curiously observe, the week of the concert, that the size of the choir has conspicuously grown. At the dress rehearsal the space is filled with a few dozen new faces I have never seen. It turns out that, in addition to folks being sick or travelling over the weeks, there are a good deal of members who have been part of the choir long enough to have performed the Requiem in seasons long past, and don’t bother practicing music they already know intimately. Years and decades: I have difficulty thinking about such timescales. The orchestra and soloists, looking peculiarly mortal in sweaters and jeans instead of resplendent dress, can and need only rehearse once with us.

Some concert venues impress on you their magnificence even before you enter, with exteriors featuring bold structural forms and immaculate gilded decorations, their presence visually supported by prominent sight lines in the city. If Carnegie Hall ever enjoyed such halcyon days in Midtown, they are now long gone. It is hard to identify from more than a block or two away, the surrounding blocks overgrown with concrete and brick and glass. The current scaffolding that cloaks the building, set up for perennial restoration work, does it no justice either. As it is crammed into a fraction of a block, many of the facilities—the plumbing that supports the spectacle—have been built up instead of out. (Indeed, the Hall itself is actually a jumbled amalgamation of three buildings, each of which has its floors built at different heights from each other.) The dressing rooms are therefore six floors above the performance hall, crammed in between administrative offices and storage facilities, the floors a delicate composition of nooks.

On concert day these rooms look like a classroom during recess. Singers sit against the walls and pillars, charging their phones, their heels and flats and dress shoes off. Good Samaritans share cough drops, trail mix, and hard candy. I am eating an egg and cheese on a roll from the bodega across the street, hoping my stomach doesn’t get upset. Our manager is ruthlessly efficient, getting us into formation in two minutes flat and warning us not to wave, shout, interact with the audience in any way whatsoever because she will shoot herself if we do.

On stage, any attempts to connect with the audience prove futile. This is not just because you’re doing what you’re told. At least in much of the idiom of classical performance arts, the auditorium is designed for isolation, a scaled-up one-way mirror. The overhead spotlights broil you, and everywhere else the lights are dimmed, so you can’t see. The acoustics are such that the walls naturally amplify what’s emitted from the stage, not vice versa. Attention could not be more polarized. What I hadn’t at all expected, though, was how small the concert hall looked from the stage. With the contrast in lighting and scrupulous layout of the balconies, the same open space that feels like a chasm from the seats becomes compressed and flattened—maybe another clever design decision.

This reduction in depth and intentional alienation, maybe, helps explain in part why I don’t have many recollections of the performance itself. Memory, anyway, has a tendency to lose its integrity in the flow state, that trance of expertise, when your mental space narrows and all you think about is execution. What you recall in hindsight is more a compendium of instances where you were distastefully brought out of that state. The audience was enthusiastic, maybe overly so. Someone whistles and claps before the final movement has finished. The strict decorum in classical music performance is one of those things that makes sense as an implicit social contract between stage and audience, but nevertheless feels unusually stringent and suffocating to the outsider, and so while I cannot fault the hapless friend who presumably just embarrassed themselves at their first classical concert for trying to show their support, I also become severely annoyed at their disturbance of the peace. When the soloists sing alone I follow raptly, as neither spectator nor accompaniment but something in between, having come to know their melodies so well I may well have been able to sing along with them, and I have to remind myself to snap back in for the next cue. Sometime after the intermission I become aware that, standing in my Amazon Basics dress shoes, I can no longer feel my toes. During the finale, apparently one of the choir members faints, a few measures from the end, but almost nobody notices, so intense is the music, and anyway it turns out she was fine.

It was only then, half-aware and singing with over two hundred others in a hall of thousands, that I finally began to grasp the larger picture. I stared into that dimmed purgatory between the stage and seats and came to inhabit it. I was reduced to my voice, a purely auditory phenomenon. We were not so much people as we were musical forms, forms separated by lines that quickly vanished, unifying to produce a singular power, coordinated by a shared and learnt consciousness. I viscerally sensed all the infinitesimal details that made up the whole: the crispness of every beat, the intentionality behind each note, the meticulous blending of harmony across disparate forces. This was the apotheosis of musicianship, a sweetness I had not quite known before. How blessed I was to taste it, if only for a moment. Thousands of man-hours and twelve weeks of work, for one concert, over in two hours.

I was lucky enough to have several friends come out for the concert, especially considering that attending carried a substantial opportunity cost in terms of other Friday night NYC activities one could be doing. Unfortunately, the setup of Carnegie Hall is not well-suited for post-concert gatherings, offering no reception areas or photo spots where the performer and plebeian may interact. The weather outside was typical April, cold and windy and rainy, and we settled for taking some disorganized group photos under the scaffolding. I left with a little hollowness, feeling that I hadn’t spent enough time hanging out after and hadn’t spent sufficient effort expressing my thanks. The social dynamic of the choir itself, too, is characterized much more by the mingling of small groups of friends rather than open extroversion, and so the post-concert social held across the street felt strangely alienating. I took photos with the director; sipped on some beer for my aching throat; and mentioned some older folks about my job as a developer, for which one responded that AI was going to automate my job soon, and that I should consider being a sex worker. No experience comes without regrets, or peculiarities, I guess.

Two months after the concert, I find myself back in the same position I was in a year ago. I’ve been enjoying lots of shower singing, and still have work to do to bring out a vibrato from the straggly caprino I had in my senior year of college. In many ways, I view singing as a peculiar kind of endurance sport, a shape of hobby with which I’m often preoccupied. Choral seasons are notably cyclical, with an off-season during the summer: I have a race and concert calendar to manage. To sing at high tessitura over several hours demands surprising vocal stamina, one that can be trained through experience. There’s an obsession with execution and a focus on key principles—tempo, cadence(s), pacing—which are all grounded in developing a better understanding of the self. The volunteer choir, on top of that, is an honest and sincere expression of dedication, not only from its constituents, but especially so from its leaders who devote disproportional time outside of their day jobs for often thankless responsibilities, year after year, though it remains to be said which of their careers they find to be more “real”.

More endearingly, I find that singing is an activity of romantic banalities. There are moments in the spotlight, but the real value comes from what’s hidden: the love for the process itself, a continuum of unsexy commitments. It is so natural, too: just as we instinctually know how to run, we find ourselves unconsciously humming earworms, crooning along to pop stars, and bleating out polytonal Happy Birthdays. It is one of the most universal human behaviours, a reflection of our innate disposition to art.

The arc of life is one of phases, milestones, projects, and adventures, each of which unleashes new forms of magic. There is obvious magic, certainly, in the enlightening satisfaction and ravenous applause after a performance done well. Far more commonly, though, the magic to be found in our lives is magic which we have to compose ourselves, the kind that must be harvested by finding meaning and fulfillment in the routine, that ongoing series of successive fifteen-minute increments. It’s the kind of transient magic that persists only in shards of memories post-hoc—the faint purpleness of the dusk on those Tuesday nights, the rustling of leaves in the church courtyard during break, the call of a mourning dove perched out of sight—but manages never to fade over decades, remains fresh in perpetuity.

I sing today as I shall tomorrow, in search of that continual magic. My days, strung together, form an aleatoric melodic line, dissonant at times, fortuitously harmonious at others. Quietly, I spin up another rhythm to decorate it.