Snow and Salt

ego, money, and dancing in the mountains

Not long ago, western Utah was underwater. This part of the state lies in the Great Basin, an endorheic watershed, a fancy way to describe an expanse of land that is devoid of any outlet to the ocean. With no hydrologic ins or outs, it’s no surprise that the Basin’s area today mostly coincides with a vast stretch of desert that hosts such welcoming attractions as Death Valley, U.S. Route 50 (named “the loneliest road in America”), and, maybe the most desolate destination yet, Burning Man.

Twenty thousand years ago, however, things were quite different. Endorheic watersheds can host pluvial lakes, bodies of water formed by accumulated precipitation whose sizes are wholly dependent on the delicate balance of rainfall and evaporation. During the last major Ice Age, when glaciers roamed the Earth, the climate was far wetter, and these lakes were significantly larger. It so came to pass that there lay a Lake Bonneville, named after some old dead white man who had nothing to do with its discovery. Bonneville stretched across the state, crossing into Idaho and Nevada, and held twenty times the volume of water contained in all the glaciers in the Basin. But its dominion would be short-lived. By the time the Younger Dryas rolled around, the climate had become significantly drier. Bonneville shrivelled, dehydrated, turned brackish. For more than ten thousand years it has looked much like the body of water it is today, the Great Salt Lake.

Other remnants of this lost sea exist, too. By the Wasatch and Oquirrh mountains, perched to the east and south of the Great Salt Lake, one can see horizontal markings and little setbacks in the cliffs marking prehistoric shorelines. And much of the Basin, seen from space, is marked with broad stripes of white, salt flats that stretch north to south between the ridges and mark the sites of dried-up reservoirs like geologic footprints, or tombstones.

In 1847, in exodus from the Midwest and propelled by a vision, Brigham Young and his Latter-Day Saints arrived in the Great Salt Lake Valley and found it unpopulated. Four days later they had begun drawing up plans for the Salt Lake Temple. Today Salt Lake City anchors the Wasatch Front, an area of human buildup whose extensive sprawl is geographically impressive in its own right. Pinched in between the Oquirrh Range, Great Salt Lake, and Utah Lake to the west and the Wasatch Range to the east, the development, taking the path of least resistance, expanded north and south. Today, serviced by the gloriously wide lanes of Interstate 15, the Front stretches along the mountains for well over one hundred miles. Though much of it up close is that typically indistinguishable, staidly kitsch American suburbia, it’s a sight to behold from a good vantage point. During the day, it appears as a level sea of grey, a sweeping vale of street grids, framed on both sides by peaks that, when the sun hits at the right angle, appear impossibly majestic. The few skyscrapers downtown are dwarfed so thoroughly you wonder why humans even bothered building them. But it’s more magical in the nighttime, once those peaks cloak themselves in darkness and blend into the sky, as the glowing of tens of thousands of streetlamps, windows, and vehicles forms a blanket of lights that, when filtered through the restless warm air in the valley, twinkles from afar like a human-scale nebula. Mormon temples, on hilltops and illuminated in pure white, glow like quasars. Steam emitted from factories in the distance looks like drifts of interstellar gas. The well-to-do up on Cottonwood Heights must have it nice.

The glaciers, for their part, shaped Utah’s geography too. They carved seven parabolic troughs into the Wasatch Range, steep and deep valleys formed by the movement of cubic miles of ice over millennia. Littered with cirques and moraines, these canyons are immense trenches dug into the mountains, their deceivingly narrow openings concealing what’s inside. In the summer, grouse, moose, and bobcats, and mountain goats (re-introduced in the 1960s) roam the cottonwood and aspen forests. So, too, do outdoor enthusiasts: the Wasatch 100 Endurance Run weaves for 100 miles and 24,000 vertical feet from north to south every September, while the quartzite crags and erratics provide settings for world-class trad, sport, and bouldering climbs.

The real magic of the Wasatch, though, is found in the winter. Streams of temperate air, coming from all directions but most frequently the northeast, and boosted by moisture from the Great Salt Lake, suddenly slam into the Wasatch after crossing hundreds of miles of plateau. The result is orographic lift, a meteorological phenomenon whereby warmer air abruptly rises in elevation and mixes with cooler air up above. The colder the air, the less water vapor it can hold; combine that with atmospheric instability from the mingling currents, and you get snow. Lots of it. For every thousand-foot gain in elevation, average annual snowfall jumps one hundred inches. The factors that shape this weather are hyperlocal and depend on the shape and position of each individual peak. And it doesn’t get more hyperlocal than in Little Cottonwood Canyon, where the mountains are just a little higher than the rest, and which terminates at a ridge that further traps the funnelled moisture. Here, snow totals can easily double those found mere miles away. Winter 2022-23 saw the heaviest season on record, with a staggering total of over 900 inches.

Needless to say, you can ski here.

Two resorts are nested at the end of Little Cottonwood Canyon, Alta and Snowbird, Alta-Bird coloquially. They are serviced by a single road, SR-210, which winds up seven miles and 3,500 vertical feet from the mouth of the canyon while passing through no less than sixty-four avalanche slide areas. A one-day lift ticket, without discounts, costs around $200. A season pass at each resort will set you back $1600. An Alta-Bird pass, which allows you to take advantage of the gates and traverses between the two, the big-mountain vibe of the Bird plus the legendary skier-only haven next door, saves you exactly zero dollars. (It is $3200.) By comparison, get an Ikon Base Pass Plus, the mega-season pass bequeathed to us by Alterra Mountain Company, for $1200—actually, only $800 with a college discount—and you can also still get a taste of the honey, with five days combined across both resorts. A bargain for the visitor.

It was only natural that I, an adventurous well-to-do young educated worker with a propensity and healthy budget to spend, what the consultants identify as a target demographic, was also tantalized by the promise of challenging terrain and fluffy powder, breathtaking open bowls and thousand-foot couloirs, perfectly-spaced glades and serendipitous bluebird afternoons. In January 2025 I, too, made the trip with a ski buddy, dragging our equipment bag through airport walkways; riding through town in a compact crossover rental; oversleeping in our suburban Airbnb every morning (being unwilling to splurge on slopeside lodging) but still leaving early enough to snatch one of the last remaining spots in Snowbird’s overflow parking lots; boarding the chairlifts each morning with two Clif bars in pocket (tolerable substitutes for the overpriced lunch that’s served at the lodges, and easy to consume); inhaling carb-heavy burgers for dinner and spending the evenings lying catatonic in bed, half-watching FWT highlights and dreaming of weaving down the mountain and sending it at mach fuck like the pros; and finally packing up in a McDonald’s parking lot by the airport on a cold evening, gear left to dry on the pavement as we cram clothes back into our suitcases.

The skiing, it goes without saying, is excellent, the kind of “good stuff” that can establish you as someone who knows what they’re talking about, with more than forgiving conditions that let you push your boundaries and romp around. Every hobby offers its own little world unto itself, a parallel universe to slip into, but with skiing this feels especially true. This is not least because there’s often a healthy amount of travel involved: flights, cars, shuttles, gondolas. The city dweller may well see more trees on a ski trip than they will the rest of the year. The physical exertion must also add to the distortion of memory: if you aren’t completely spent, you probably haven’t done enough. The culture is rich, facilitating your participation in a fantasy that you discover incrementally. The extent of specialized vocabulary, terminology, and lore, I think, is a good proxy for how immersive a world is. Indeed, one only need to skim through an Outside article, watch a YouTube edit, or just talk to anyone else who’s been to Alta-Bird to hear of the mayhem of the Cirque and High Traverse, the lines off Wildcat and Gad, the bootpacks and backcountry routes, the mythos of Chad’s Gap and Tanner Hall’s ankles. For me to try and contribute something to the canon here is not worthwhile.

What sticks out most of all, though, are the ludicrous amounts of sheer fun. Life really seems to become lower-dimensional, collapsing to a subspace spanned by play, energy, joy. Each day on the mountain is truly simple. Your identity is reduced to basically two things: the garb you wear and your level of ability. Clothing and gear will completely conceal your body, to the extent that the way we identify people is by the color of their jacket and how cool (or not) they look on the slopes. To be a “gaper” or “jerry” is simply to make the blunder of failing to meet either criterion. You can be a kid, roaming around a playground but exponentially larger, finding stashes and secrets not unlike the way you’d explore an open-world video game. Or an adrenaline junkie, precisely determining your exact physical or mental thresholds while tackling increasingly questionable routes. Or a performer, showing off under the lifts—for it sure feels like the rush of skiing is the closest I’ll ever get to dancing as I pilot my body with instinctual confidence through the snow. You could be all three at the same time, and the world will still feel refreshingly basic, new, straightforward, the product of the one-track psychological state you’re in. Everyone contains multitudes but it can occasionally be quite pleasant to pretend we don’t.

Here, perhaps, is a rare example of an expensive activity that’s worth it, of a pasttime that occupies a premium tier of hedonism accessible only to those willing to spend while being decidedly more palatable than its peers therein (like drug abuse), of buying happiness. (To wit: have you noticed how your wealthy friends somehow all know how to ski really well?) No wonder, then, how the end of a ski vacation can be like a comedown. In retrospect it feels like trying to recollect a dream, the past few days already blurred in hindsight, quickly shelved as quotidian responsibilities again settle in. The experience is scarce and stark and fleeting, a trip that, once over, instantly feels timeless—outside of time, a cold reverie that lasts forever and ends before you know it.

In the winter a remarkable organism emerges in the Little Cottonwood Canyon and crawls slowly through the valley, its size gargantuan and growing every year. Though it often comes suddenly and vanishes within hours, the patterns of its arrival do follow some regularity. Indeed, there are some situations where we can almost assuredly forecast its appearance: weekend mornings and evenings, usually during the half-light of dawn and dusk, and snowstorm days. I am referring to the red snake, the chain of vehicles stuck bumper to bumper in SR-210 named for its stream of taillights. It may well be the only instance of gridlock in the state, given that development in the rest of the Watasch Front is, remarkably, spread out enough to rarely overwhelm the car-centric infrastructure, a miraculous case where the American Dream of automobile ownership mostly works. For most of the trip I find myself enjoying driving, a feeling I have scarcely experienced since getting my license.

The thing about roads is that they catastrophically fail to handle surges in demand; their peak capacities are conspicuously restricted by the size of our obnoxiously large, space-inefficient cars. And in Utah, there is no better example of a surge in demand than a horde of tens of thousands of zealous weekend warrior pow-chasers concurrently crowding into the single hapless lane that winds up the canyon, all thinking they have woken up at an unholy enough time to beat the traffic, but finding themselves so mercilessly wrong. The weather, obviously, exacerbates the chaos. The skiing conditions are the best precisely when driving conditions are worst, and so when you slither in the red snake, you slither through inches of sleet and slush. In an attempt to mitigate the slideouts that invariably happen, the Department of Transportation (UDOT) will sometimes set up checkpoints to only allow through traffic with AWD or winter tires. But this essentially creates a new chokepoint right at the entrance to the canyon, which is arguably even worse. During the worst storms, an “interlodge” is declared and the roads are closed. Sometimes the resorts will still open, and with the plebeians all locked out, the gentry staying slopeside get the mountains all to themselves.

The Saturday morning of our trip, Alta reports thirteen inches. It is going to be a calamity. Having woken up too late to beat the wave, my buddy and I decide that we would rather languish in traffic as passengers on a bus than as occupants trapped in a car, and take a 7:30 AM Park-n-Ride shuttle—one of a few pilot routes offered, departing every half-hour, pretty sad as far as bus networks go but an alternative to driving nonetheless.

Shortly after 8:00 AM, we join the tail of the snake. We have just exited I-215 onto 6200 S, and it is five miles to the mouth of Little Cottonwood. The snowfall is still heavy, around two inches an hour. The bus is quite full, with maybe twenty-five other riders who must have thought similarly to us. Everyone has brought their own equipment, but the bus’s interior hasn’t been equipped with any special racks or storage spaces, so we all individually find our own awkward ways to manage our inventory. Skis are dubiously jammed between seats, boards are shakily propped up against windows, poles clatter with the vibration of the engine. I need to pee.

One hour later, we have travelled one and a half miles. The opposite lane is empty. There are no cars heading in the other direction. I open up r/UTSnow on my phone and read the trending posts. The top one is written by a Redditor who had gone to a later Park-n-Ride stop only to encounter a full bus, settling for standing room on the next one. The post is titled, “There is no incentive to ride the bus”. The author is probably on this bus. Another post is a collection of screenshots of UDOT traffic cam feeds showing miles of stationary traffic. It’s titled “Good luck”. I get a text from a friend, who’s in NYC and not even skiing right now, asking if things are really as bad as he hears. Alas, there are no express bus lanes in the mountains.

By 10:30 AM, we are close to the mouth, about to clear the key bottleneck: a cursed stoplight where SR-209 merges into SR-210, after which the flow of traffic is glacial rather than constipated. Sadly for me, this respite will come too late. Time is up, and I have reached the physiological point where I need to go so bad my mental functioning breaks. I can not think of anything other than the capacity of my bladder. I waddle to the front and ask the driver if he can let me off for a minute or two, after which I’ll catch up to the bus. He coolly agrees and thereby saves my life. He shifts into park and suggests that I go and crouch by the front right wheel well, which is the most discreet place next to the vehicle. This is desperate and ridiculous and I do it. I am on my knees on the road in a snowstorm wearing ski boots and dressed in Arc’teryx and pissing under a bus on a Saturday morning. Each second stretches into eternity. I tidy up and walk back on and people are staring at me, but there is no judgment in their eyes. The SUV in front of us hasn’t moved.

We finally get to Alta at 11:30 AM. In all fairness, if we had driven we probably wouldn’t have saved much time, and this was still about twice as fast as walking. The afternoon is well worth it. Yelps of delight rise from the woods, GoPros are mounted on helmets all over, and the lifties are playing “Red Barchetta”. A private instructor is yelling “turn, turn!” to his student, who’s presumably using the fresh snow to help tackle their first chute. Yeah, bud. $200 an hour to get yelled at to turn.

Delayed lift openings and the continuous snowfall means it’s still deep all around. So deep, in fact, that I am painfully reminded that I don’t actually know how to ski powder, not on my 95 mm all-mountain skis anyway. It’s enticing to envision yourself floating atop untouched snow, but the reality is that unless you know the right technique, maintain enough speed, and stay on steep terrain, you will sink and come to a standstill, after which you have to ashamedly wade through knee-deep snow like a seal on land. In these whiteout conditions I can’t tell where I am going, so I spend a decent amount of time executing controlled wipeouts and looking pathetic. I am Jerry now. I realize that being able to make my way down the blacks is just the first step. The rest is refinement, a lifetime of incremental improvement, of developing the skill to make it look easy. Granted, there will always be more tricks to learn and a local with better style than you. But the reward is in trying.

SR-210 is closed in the early afternoon as crews perform avalanche mitigation, so the lifts run for an extra half hour. I take full advantage of this and share a few chairlift conversations, as sporadically tend to happen. There’s a college student from UVM who shares my admission that as East Coasters, to ski here requires relearning our technique from virtually scratch; a businessman complaining about how expensive it was to take his client and kids out to Deer Valley for a weekend; a ski bum who nabbed second chair of the day and has icicles hanging from his nose and beard; a senior remarking on how forty years ago, prices were an order of magnitude cheaper but everything was an order of magnitude crappier, too. Few are in a rush to go back down the canyon, so the lodge is crammed with sweaty après-ski hopefuls, sipping on $10 glasses of beer and watching the skies darken.

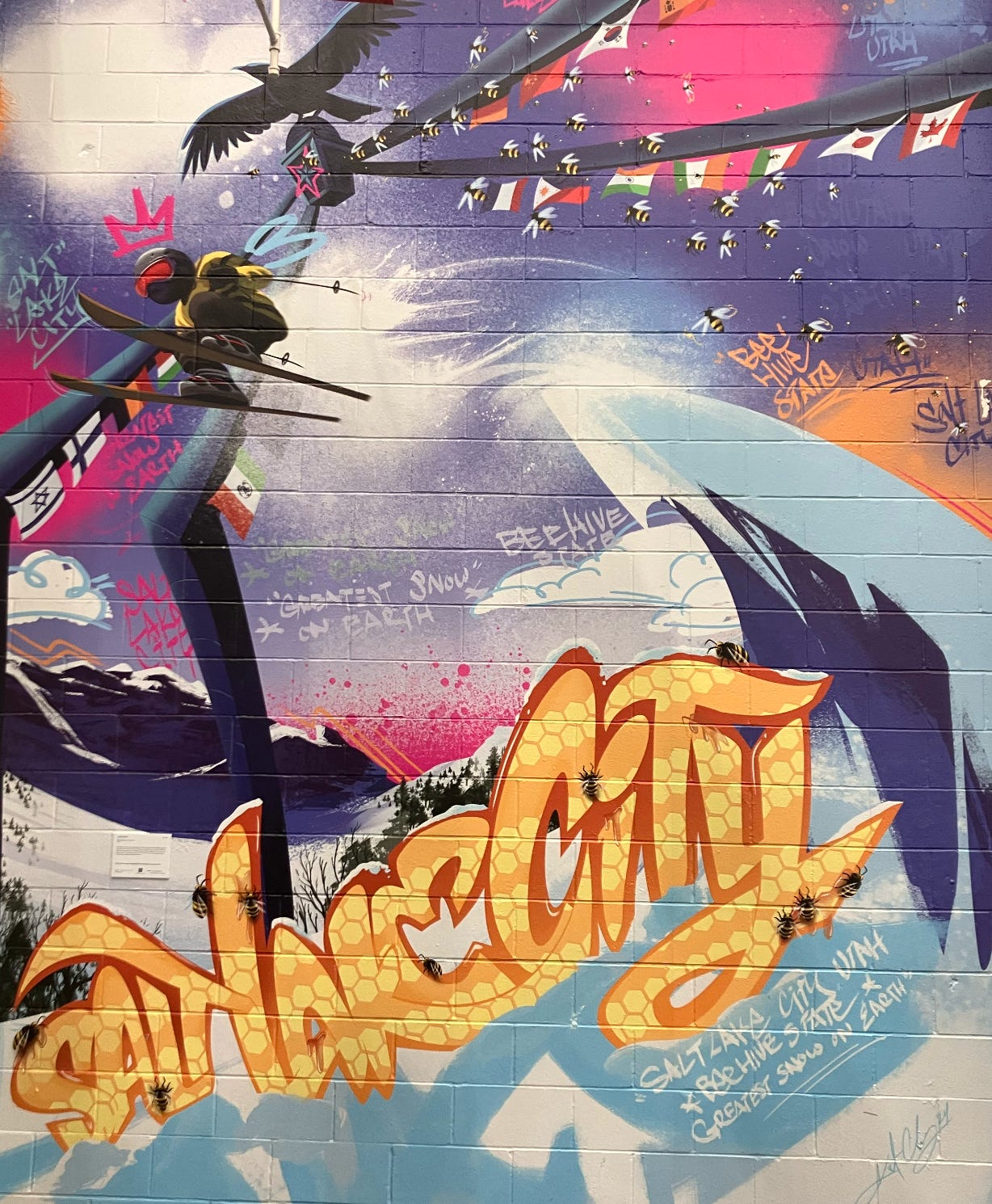

Skiing culture is not particularly on ostentatious display in Salt Lake City proper. It’s a bit moot, really, because the activity has saturated the populace to the point where it is effectively an unspoken collective way of life. Nobody talks about skiing and snowboarding as if it were a special quirk of theirs, because everyone knows that everyone skis and snowboards. Rather, it’s small talk, the same old, treated the same way San Franciscans treat hiking or New Yorkers treat dining. Though I did see a pretty wicked mural in the city. It was located at the entrance to a Walmart. You could only see something like that in SLC.

Utah doesn’t need any extra publicity anyway. The allure of the Ikon Pass, which provides access to four other ski areas in the Wasatch in addition to Alta-Bird, and its rival Epic Pass, which gives a holder unlimited days at Park City, one of the largest ski areas in North America, have significantly subsidized the pilgrimage to SLC. These passes have been massive business successes. In winter 2018-2019, the year that the Ikon Pass debuted, an estimated 3.5 million skier visits were made in Utah. By 2023-2024, that number had doubled. Skiing culture, pushed forward by Instagram ad campaigns and aggressive M&A dealmaking, has become more mainstream than ever, and I am, obviously, part of the trend here.

To a first order approximation, this sounds great. Skiing is getting democratized, and it’s easier than ever to visit premier destinations and form experiences to last a lifetime. Our aggregate joy is increasing. The strain of this growth, however, has made itself apparent as well. Prices for lift tickets and passes have ballooned, and when combined with the prices of lodging, transportation, and purchasing or renting equipment, the overall cost, even when being frugal, will be indisputably unsavory to many. It’s fair to ask if this democratization is, in our product-obsessed economy, just another example of the creation of a new luxury opiate.

These eye-watering prices nowadays stand in complete juxtaposition to the lives of the humans that actually make it possible. Many of the jobs pay around $20 an hour, and with the rising cost of living, employees increasingly find themselves priced out of the very livelihoods they are responsible for sustaining. The week we are there, the Park City ski patrol union (you know, those who ensure you don’t die) goes on strike, demanding a bump in their base pay from $21 to $23 an hour. Vail Resorts Inc. (NYSE: $MTN), the conglomerate in charge of the mountain, attempts to fly in patrollers from other resorts they own as negotiations drag on. But this only does so much. In the middle of the holiday rush, Park City is 20% open. Visitors encounter hour-long lift lines and begin to duck ropes. Some wealthy vacationers have had enough, and begin to complain on Twitter. This is the “oh shit” moment for Vail, and after that it isn’t long until an agreement is reached.

To alleviate the curse of the red snake, UDOT has proposed engineering an eight-mile gondola system ascending Little Cottonwood Canyon, with a total construction budget that has grown to over $1 billion. Since its inception the project has been met with vehement opposition and litigation from local politicians, advocacy groups, and public opinion, citing among other factors the environmental disruption, absurd cost, and undercurrents of corruption. The easiest solution, maybe, would be to expand the bus system, but this is also a hard sell to the thousands already hooked on the taste of car dependancy. (In fact, Salt Lake City has built out an impressive set of bike lanes and a light rail system, but that only goes so far when the bike lane is just a line of paint on a hostile stroad, and the trains come every 15 minutes.) What’s clear is that the chronic presence of the red snake is representative of an infrastructure system pushed beyond its limits by unexpectedly voracious growth, with no easy method to build the problem away.

I don’t have a firm understanding about the geography of the Great Basin, the demographic evolution of Salt Lake City, or the meditations of an experienced skier, though having some cursory familiarity with those topics certainly proves useful when reflecting on a ski trip. Aside from all this intellectual rumination, in any case, at the end of the day I think the most important exercise is to ask myself how I intuitively feel about the experience I’ve had, and when I do, I find that one of the feelings that lingers most is that of guilt. Or something a bit more amorphous than that, a state of general compunction. Isn’t it ironic that by going to ski, the emissions I generate in transit directly contribute to the poor air quality that often smothers the Great Salt Lake Valley, and the rising temperatures that pose an existential threat to the very activity? Am I contributing to the local economy, or just enriching an industry of exploitation and furthering inequality every time I buy a $16 grilled cheese at the lodge? Do I generally feel bad about living simply, hedonistically? (Classic of me to feel discomfort over a state of mind that doesn’t involve overthinking.) Then again, a life lived without guilty pleasures to me sounds a lot to me like a life too staid. For the time being, I stay complacent.

A dire future, though, seems more and more likely. I see it clearly.

Temperatures will rise and Salt Lake City’s climate will gradually turn into Phoenix’s today. Snowmaking systems will be installed and lower mountain runs silently removed. The snow falling on the Wasatch will be just as intense, but wetter, like Sierra cement, gradually losing its greatness, then ceasing to be snow at all. Alpine terrain openings become increasingly rare as the snowfall drops below what’s needed to build a base. Rocks and boulders, once buried for months on end, begin to peek their heads out of the snow, soon becoming perennial features. Traverses become hikes. Roped-off areas become permanent closures. The season at Alta-Bird shrinks, week by week. One year, it is finally announced: resorts are to cease winter operations indefinitely following closing day. For this monumental farewell, the red snake will make perhaps its last ever appearance, in full force. The day will be jubilant and sorrowful, a finale that parents will tell their children about years later.

The resorts won’t go out of business, though. They’ll keep spinning their lifts in the warmer seasons, catering instead to mountain bikers and sightseers too lazy to hike. Vail and Alterra will be doing just fine, announcing each year new expansions of indoor skiing centers and parks, plus new luxury destination openings in Alaska, Greenland, and the Arctic Cordillera. When an elusive snowstorm hits Little Cottonwood Canyon every other year, hardcore fanatics, equipped with their backcountry gear, will still make the trek, skinning up the mountain and passing the remnants of abandoned lodges. But for the most part, the people of SLC will move on to other hobbies, other ways to be incessantly outdoorsy. Decades of tradition and joy, what was once a cultural centerpiece, will become a thing of the past for good, the stuff of legend. Life, though, will always adapt.

If that is the inevitable end, an ultimatum beyond our control, so be it. If anything, respect it. Let us remind ourselves of that platitude, with skiing or otherwise: if we know our time is limited, we should cherish it all the more. There’s something very beautiful about impermanence, and we should not overlook that beauty. Let us hope, and, if we can, fight for a future where we may keep doing what we love—but let us also remember to play, harness the certainty of the present, and, of course, continue to blissfully indulge in those boundless dreams of powder.